The latest proposed 18-story $1.4 billion telescope addition to the Mauna Kea Summit was bound to create a tipping point in Hawaiian history.

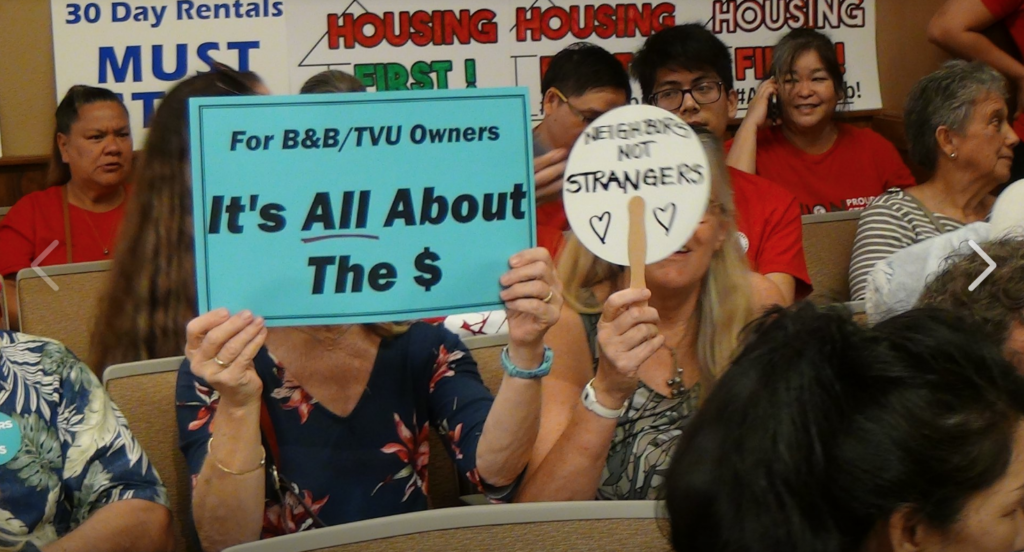

It’s no secret that Hawaii residents constantly have to protest against the intransigence (unwillingness to listen) of big government and/or private corporations who have the backing of big government in many projects.

Yes, the State of Hawaii has significant and purposeful checks and balances in its environmental review process – Environmental Assessment ( EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) – for major projects. But adherence to the entire prescribed rules and regulations and process is inconsistent.

Project owners get to choose and compensate their own environmental review company. Environmental review processes are regularly pushed through the status quo food chain despite public concerns over multiplier negative impacts like traffic, loss of fertile farm lands, social upheaval, fiscal impropriety, cultural damages, and so forth.

“Consultation” and “Public Participation” with the most affected parties are mandated core requisites in the environmental review process, but often ignored and subverted in real life.

Hawaii Administrative Rules (HAR) Section 11-200-5 requires an agency to “assess at the earliest practicable time the significance of potential impacts of its actions, including the overall cumulative impact in light of related actions in the region and further actions contemplated.”

HAR §11-200-9(1) explicitly states that the agency must also consult with “those citizen groups and individuals which the approving agency reasonably believes to be affected.”

The intent of the term, “consult” in the context of the Hawai‘i EIS Law is clear. The clarification is found in the 1997 Guidebook for the Hawai‘i State Environmental Review Process, prepared by the Office of Environmental Quality Control (OEQC):

Pre-assessment Consultation

Prior to preparing your draft EA it is important to consult with the community regarding your proposed activity as well as agencies. [emphasis in the original] Groups, individuals and organizations that have expertise in the field, have an interest or will be affected by the activity you are proposing should be consulted. Immediate neighbors or neighboring landowners must be contacted. Consultation with the local planning department is required. The local planning office can also direct you to other necessary agency contacts. [OEQC Guidebook, p.13]

“Consultation” with the affected community is the first of several elements of public participation in the environmental review process established under Chapter 343.

“Public participation” is the core value to rational environmental management and has long been recognized as good policy. It is explicitly identified as a founding principle in the legislative findings that preface the environmental review law:

§343-1 Findings and purpose. The legislature finds that the quality of humanity’s environment is critical to humanity’s well being, that humanity’s activities have broad and profound effects upon the interrelations of all components of the environment, and that an environmental review process will integrate the review of environmental concerns with existing planning processes of the State and counties and alert decision makers to significant environmental effects which may result from the implementation of certain actions.

The legislature further finds that the process of reviewing environmental effects is desirable because environmental consciousness is enhanced, cooperation and coordination are encouraged, and public participation during the review process benefits all parties involved and society as a whole.

Both the Rules and the Guidebook provide that consultations with the community should occur at the outset of the process, prior to assembly of the actual draft EA. This assures that both concerns of the community and its intimate knowledge of the site of proposed actions are understood and incorporated into the planning process.

Furthermore, HAR 11-200-9(C) requires agencies proposing an action to analyze alternatives to the nominal project proposal in the environmental assessment.

Consideration of alternatives is another core element of the environmental planning process and offers one of the key tools available to achieve the purpose of environmental impact minimization. The OEQC Guidebook includes specific instructions regarding the discussion of alternatives:

Consider alternative methods and modes of your project, and discuss them in the draft EA. Select the one with the least detrimental effect to the environment. Alternatives to consider include:

• Different sites: is one site less likely to infringe on an environment that needs protection, such as a wetlands or an historic district?

• Different facility configurations: is one configuration less likely to intrude on scenic view planes?

Alternative analysis should include input from the community. Community members may be aware of concerns and impacts that make a particular alternative more or less desirable. [OEQC Guidebook, p.15]

The Guidebook also offers insight into what’s expected in an EA in the way of alternatives analysis in its discussion of questions to ask when reviewing an EA.

Are alternatives to the proposed project (including no project at all) adequately explored? Are there other ways to carry out the project which may be less damaging to the environment? Are different designs or approaches discussed sufficiently? What basic improvements can you suggest? [OEQC Guidebook, p.9]

Thus, alternatives to discuss include not just the no action case, but also actions of a significantly different nature that would provide similar benefits with different minimal impacts, different designs or project details, different locations, different facility configurations, and even the alternative of postponing an action pending development of a more viable proposal. (Bold added for emphasis)

The Mauna Kea’s 18-story telescope’s environment review process and other related procedures inevitably became more complicated through the years.

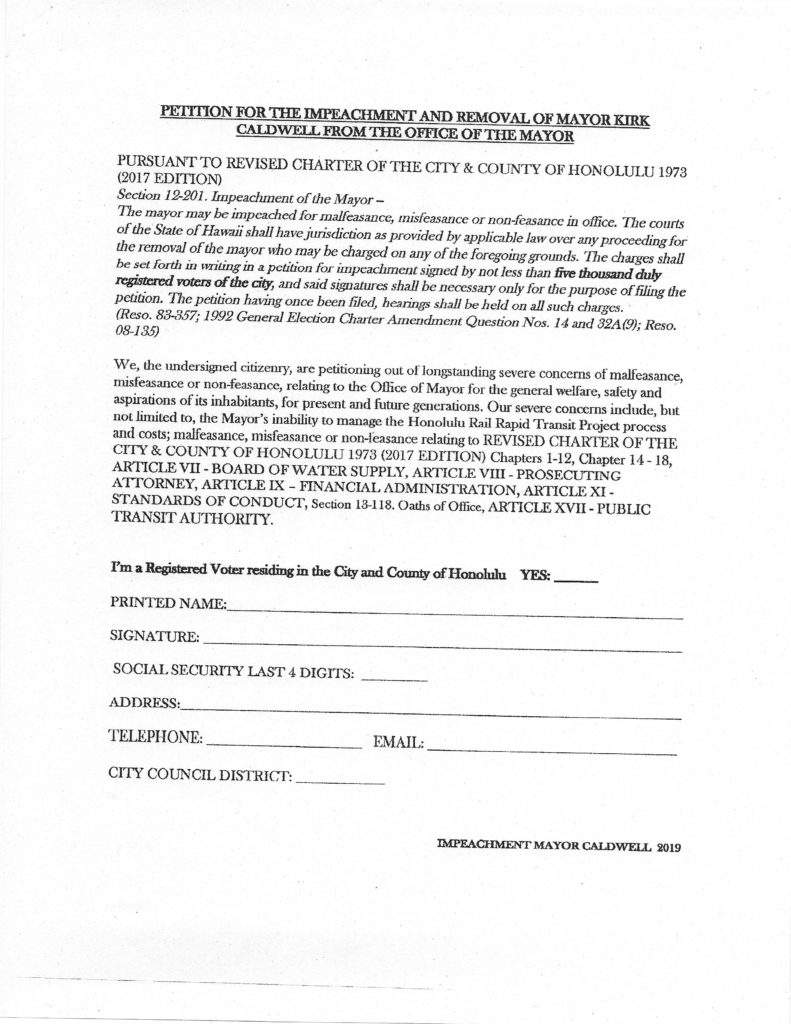

Opponents were forced into the courts to be recognized. Conflicts of interests relating to the State Hearing Officer relating to permit issuance were fought over. and so on. Yet, the powers-that-be continued its intransigent behavior. Subsequent elected officials continued the same intransigent pattern.

History shows that in August 2008, Star Advertiser’s Kevin Dayton reported:

“U.S. Sen. Daniel K. Inouye is pressing to have a huge new telescope project built on Mauna Kea that is almost certain to be controversial among Native Hawaiians. But he is also proposing steps such as scholarships for Hawaiian students as part of an initiative to garner public support for the project.

The loss of the TMT project to a competing site in Chile “would not bode well for us as a nation, and could very well signal an end to any major astronomy investment on American soil,” Inouye wrote in the letter.

TMT Observatory Corp. — a partnership between the University of California, California Institute of Technology and an organization of Canadian universities — selected Mauna Kea and Cerro Armazones in Chile as the two potential locations for the telescope it hopes to build by 2018.”

Kevin Dayton further reported a significant piece of information about the review process then:

“Sierra Club’s Mauna Kea Issues Committee Co-chair Nelson Ho said no one knows the “carrying capacity” of the mountain, or the point at which the development overwhelms the natural resources there.

“I think the senator is ignoring a lot of widespread sentiment that Big Islanders don’t want more telescopes on the mountain, let alone the TMT,” Ho said. “It’s a huge monstrosity at a time when there are still too many unresolved issues on the table.”

Obviously Nelson Ho, an informed and local activist’s opinions were insufficient to be acknowledged as part of the “consultation” and “public participation” review process.

A stream of public concerns from various groups and peoples would continue. Unfortunately, the TMT site had been pre-selected and pre-determined. Big government would steamroll the project through no matter what.

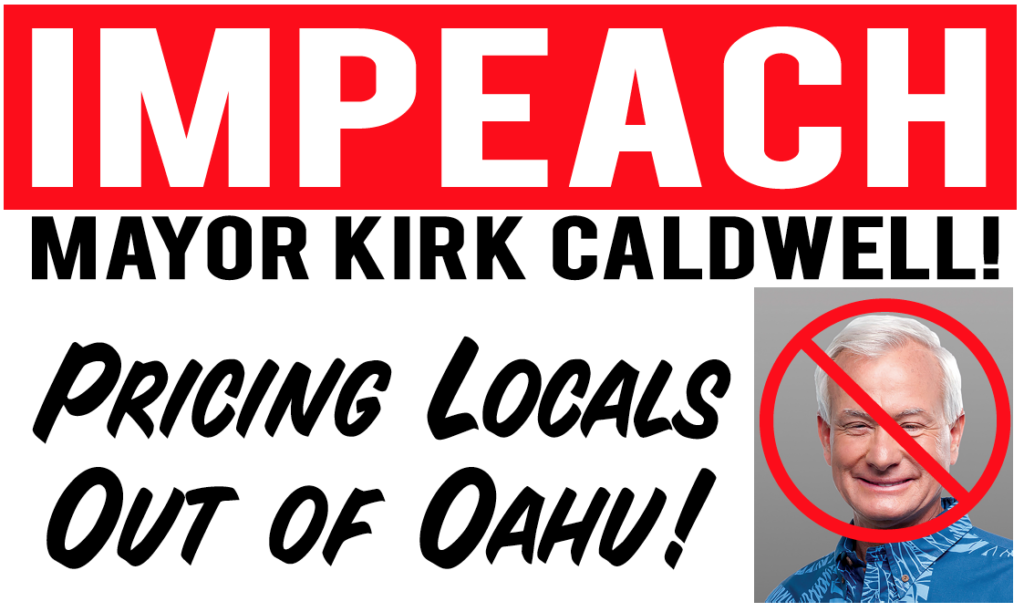

It’s time for the oligarchs of Hawaii to play fair, not strong-arm politics. The Mauna Kea project is not the sole irritation in Hawaii.

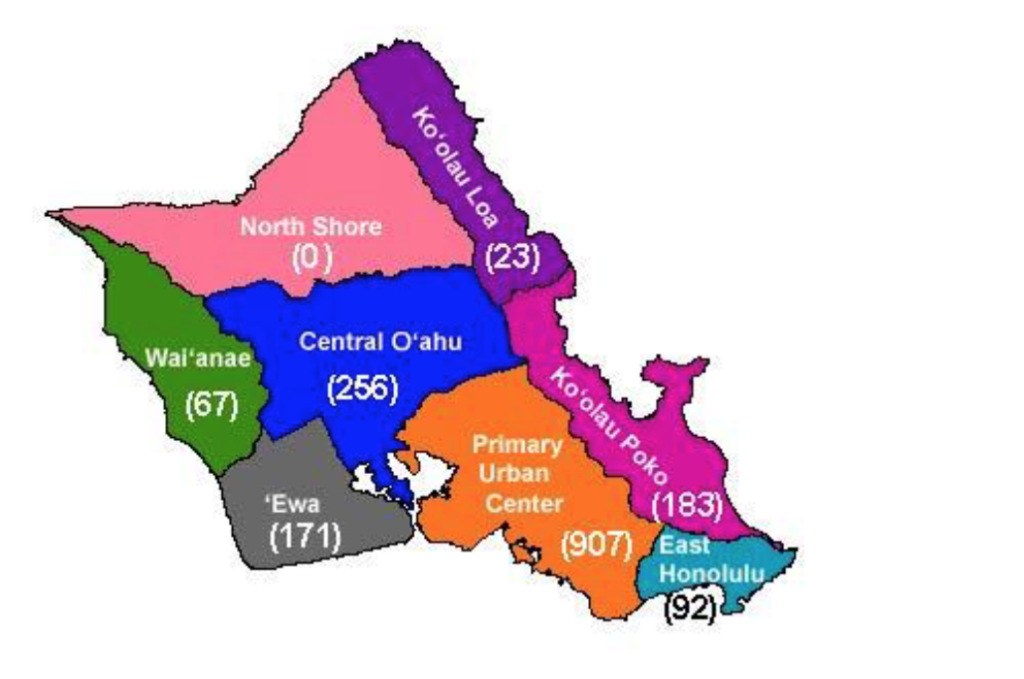

There are countless controversial decisions that are pushed through without thoughtful consideration of significant public concerns and input, like the struggling Honolulu Rapid Transit Project, the Important Agricultural Lands (IAL) Designations, the proposed Ala Wai Canal Watershed Project, Ho’opili, Ala Moana Beach Park Master Plan, Sherwood Forest Master Plan, Blaisdell Center Facelift, A&B Water Irrigation Permits, the Thomas Square Project, the Hauula Fire Station Relocation, Kahuku Wind Turbines, and so forth.

The Mauna Kea Project’s history of intransigence- – ignoring “consulting” and “public participation” during the review process also does not adequately address many other unanswered questions about Hawaii’s crown and ceded lands, the cultural, historical and social impacts, the “conservation” zoned land use and management and so forth

Yet, on July 14, 2019, there was an orchestrated display of force by Hawaii’s Oligarchs. In addition to DOCARE police, sheriffs, and National Guards, more police presence would be deployed from Oahu and Maui. The presence of LRAD, or “sound cannon,” tear gas, raid gear, batons and so on were also present as reported by observers.

Subsequently, on July 17, 2019, law enforcement arrested 38 peaceful opponents of the Project. The Governor then issued a State of Emergency through his media communications team:

HONOLULU – Gov. David Ige today issued an emergency proclamation to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the people on Hawai‘i Island and across the State of Hawai‘i, to also ensure the execution of the law, prevent lawless violence, and the obstruction of the execution of the law.

The emergency proclamation gives law enforcement increased flexibility and authority to close more areas and restrict access on Mauna Kea. This will allow law enforcement to improve its management of the site and surrounding areas and ensure public safety.

“Our top priority is the safety and security of our communities and the TMT construction teams. This is a long-term process and we are committed to enforcing the law and seeing this project through,” said Ige.

The Resistance, practicing fortitude and Kapu Aloha, has been peaceful and non violent as all visiting observers have attested to.

A fair-minded person should be extremely concerned with the chronic intransigent pattern in undermining values of “consultation” and “public participation” of the most affected parties, the flaunting and abuse of big government powers and resources towards the Mauna Kea Resistance thus far.

What may be deemed legal may not always be just or pono.

Choon James has been a community advocate for decades. She has also been a real estate broker for over 30 years. She can be reached at ChoonJamesHawaii@gmail.com Photos by Nate Yuen. Special mahalo to John Harrison, PHD UH Manoa Environmental Center (Retired).